India II

Posted on June 22, 2013

Today was a day of exploration and the temps never hit the 106 mark, so it was a much more comfortable 102 or 103. Delhi is the name given to the city as a whole, but New Delhi (the southern part of the city) is the actual capital of the country and was laid out, designed, and built by the British when they moved the colonial center of power from Calcutta to Delhi. Old Delhi is where most of the ancient sites sit and its crowded, hurly burly stands in contrast to the grand avenues and colonial Neo-Classical stateliness of New Delhi. We started at the latter.

First stop: a drive up the Rajpath (think road of the king), the broad ceremonial avenue that runs from the old Viceroy’s residence, the Rashtrapati Bhavan (the Viceroy was the Queen’s representative in India and thus its ruler during the colonial period). It’s a mix of Western and Indian styles and is said to have the most beautiful gardens in the city, though they are only open in the winter months. It is a huge building (they all are in this area, giving some sense of British might) and had 2000 people serving it during its heyday.

The Rajpath runs between grand red sandstone buildings, essentially domestic ministries on one side and international on the other,

and down a slope to the Arc de T inspired India Gate, a memorial to Indian soldiers killed in WWI.

On both sides of the avenue are lovely green parks under which families found shady refuge from the sun, some picnicking, but many sleeping. The whole area was designed by British architect Edwin Lutyens and he did many of the buildings we saw in this area. I knew I remembered his name and it turned out that he did the WWI war memorial at the Somme battlefield, a sad and haunted place we visited many years ago in France.

Just off the Rajpath is the Indian Parliament, the Sansad Bhavan, a large elegant round building second only to the Coliseum (at least according to my guide Ramakat) and the site of a 2001 Islamic terrorist attack, so no stopping allowed. Like lots of grand places, the Forbidden City and Red Square, this area is too enormous to also be human, at least in scale, and aside from those few napping families under the trees, it was impressive and cold at once.

Just off the Rajpath is a more leafy neighborhood of old white colonial homes behind walls, the residences of high ranking politicians. While they hold office they get to live in these homes and while they can change the interiors, the exteriors must remain intact and white and the compound walls must be of the red sandstone that marks government buildings. There are monkeys in the surrounding park areas and it is said that they are there to advise the politicians (i.e. they are no smarter than monkeys). The streets here are lined with tamarind trees that provide both shade and the essential agreement in many curries. In fact, it is said that an Indian woman making vegetable curry would sooner forget the vegetables than the tamarind. As you might guess, Ramakat was full of such sayings.

He also had a funny mannerism in his guide speak. It was always a question, a pause in which I was supposed to guess the answer, and then the answer. Sample:

Ramakat: Do you know why there are monkeys near the Parliament, sir?

Me: (after long pause) No Ramakat, why are there monkeys around the Parliament?

Ramakat: Because they have to advise the politicians, sir.

This sort of carried on all day and I think Ramakat may have been mentally keeping score to see if Mister University President might actually get one right.

Ramakat: Do you know why there is a wall at the back of this pavilion, sir?

Me: (pauses getting shorter) No, Ramakat, why?

Ramakat: So during the monsoon the rain blowing in sideways would not wet the emperor, sir.

This became our pattern and by day’s end wreaked havoc with my self-esteem in terms of Indian history.

It was a lot more fun to drive into Old Delhi, messy and chaotic and poor and full of humanity. Without the grand avenues of New Delhi, traffic slowed to a crawl. I couldn’t help but notice that lack of belching black smoke one sees from auto-rickshaws in places like Thailand and Laos and Ramakat explained that to combat pollution they all use compressed-natural gas, as do many buses and taxis.

Ramakat: Do you know why there is no exhaust smoke, sir?

Me: (pauses getting shorter) No, Ramakat, that’s sort of why I asked.

Ramakat: Because they all use compressed natural gas, sir.

Me: Damn…

Score one for India on getting ahead of us on smog though.

Our first stop was the imposing Red Fort, built in 1659 by Shah Jahan when he moved his capital from Agra. Most know him as the builder of the Taj Mahal, the famous white marble mausoleum for his beloved Empress, Mumtaz Mahal. Ramakat explained that his advisers worried that the grief-stricken emperor would not get back to ruling without a change of scenario and Delhi was the traditional seat of power (you can guess now how Ramakat started that explanation).

The red sandstone fort was the last holdout against the British in the 1857 Rebellion, so every August 15th, the anniversary of Indian independence from Britain, the Indian Prime Minister symbolically raises the Indian flag at the Red Fort.

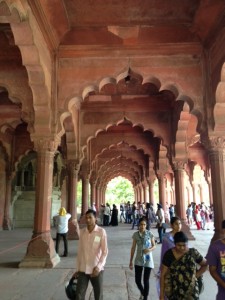

In contrast to the sturdy and fierce outer walls of the fort, once one passes through the inner gates there is a rich array of pavilions and palaces that are the height of Mogul design and creativity (Mogul is a derivation of Mongol for the Islamic invaders of the north that held India for about 600 years).

While these buildings show their wear and tear and modest restoration is underway, it is not hard to imagine them at their luxurious peak where rich inlays on marble, fanciful fountains and “rivers” flowed, and the Emperor sat on the Peacock Throne.

That building in the distance is the Elephant Gate. Visiting dignitaries would essentially park their elephants on the other side and then walk down that path to the pavilion from where I took this shot. The Moguls loved exacting symmetry in design and most of that original design remains intact, though there are colonial buildings from the British era that don’t really fit in and were erected as the seat of government before Luytens built New Delhi.

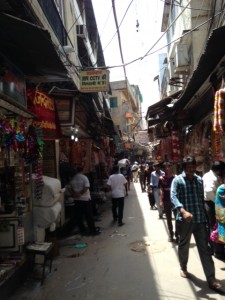

We left the Red Fort and Ramakat hired a bicycle rickshaw and we plunged into Chandi Chowk, one of the oldest and most crowded bazaar in Asia. Many of the pathways, little more than alleys really, were once canals. It is crowded and chaotic and great fun.

One can buy just about anything in Chadni Chowk and it is said (another Ramakat axiom) that if a foreigner stays long enough they will be relieved of their goods and can later buy them in the market. It is a warren of shops and workshops and one can become hopelessly lost. We had our faithful rickshaw driver who was laboring mightily in the extreme heat. Ramikat has missed few meals from what i can tell and I’m no spright, so this poor guy was working hard. When we finally stopped at Jama Masjid Mosque I doubled the usual tip ($4 instead of Ramakat’s recommendation of $2) and that drew a big appreciative smile from our driver.

I was bummed to find the Mosque closed for repairs. Built in 1644, it is the largest mosque in India and one of the largest in the world, able to hold 25,000 people.

I like the quiet and cool of mosques and after our hot sweaty touring I had looked forward to the relief it offered. Next time.

No one looms larger in Indian history (or world history in some ways) than Mahatma Ghandi and we passed the place of his cremation, the musuem dedicated to him, and this wonderful statue commemorating his 1930 Salt March, a seminal event in his non-violent protest movement.

I asked Ramakat about Indian attitudes towards the British and he answered in his usual format, except that he answered his own questions:

Should we be grateful for the railway system they left us? They built it to empty the country of resources.

Should we be grateful for New Delhi? They built it because they thought they would be here ruling us for centuries.

And so on. But he then turned philosophical and said, “But whatever their motive, we have these things and they managed to run this big country and we have to learn to run this big country better than we do now.”

We finished our day with the mandatory stop at a place to shop, though in this case it was a government subsidized center specializing in crafts from Kashmir, the beautiful northern area at the center of armed conflict between India and Pakistan. With tourism ruined because of hostilities, the government uses this center as an outlet for Kashmiri crafts people. I have danced this dance many times in Egypt, Dubai, Syria, and elsewhere. First there is the warm welcome, the “just let me show you what we have” invitation, the tea and bisquits, and soon this:

Carpet after carpet strewn across the floor. A size for every budget and in truth, they were beautiful. The salesman actually had a real passion for the carpets and the 120 families represented in the center’s showroom. He gave me a great tutorial on hand knotted carpets:

And yes, I finally relented and bought a small carpet, as I knew I would when the I took that first sip of tea.

With the afternoon ending we made our way back to the hotel. Hitting the fitness center, I looked for some sports to watch while on the elliptical. I found a bit of soccer and then….badminton, field hockey (women and men), cricket, and women’s archery. The great delight of travel is the tension between the familiar and the strange, the way another society does differently what feels so similar. In this case, by the end of my workout I was cheering along as the Indian women’s team won the bronze medal in archery by only two points on a final shot of the match. Yeah India! Who needs the Bruins playoff game? Actually, I do and will be up at 6:00 AM to see if I can follow it online.

With a shower, I was off to a wonderful dinner with new Indian friends at Bukhara, one of the most famous restaurants in Asia. But more on that later.