“How was Antarctica?”

Posted on January 20, 2023

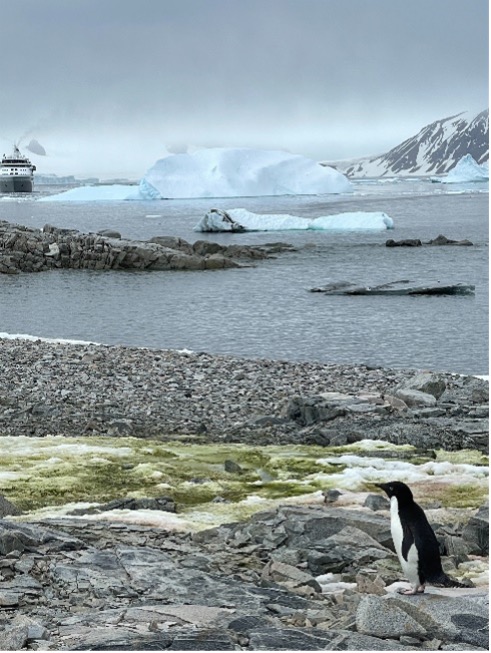

Lots of people are asking about my recent 15-day trip to Antarctica, and the answer is “Amazing!” In short order:

One of the best trips I’ve ever done, exceeding my expectations.

The animals are abundant and incredible: penguins, whales, seals, a variety of birds.

The landscapes are majestic, the weather capricious.

It was a rollicking good adventure and also quite moving.

That’s the short version, and you can stop right there and simply scan the photos that follow below or go to my Twitter account (@snhuprez) where there are lots of pictures and videos.

If you want the really extended answer, keep reading. But really, it’s pretty long and I’ve given you the headlines above.

Paul

My Antarctica Adventure: Part 1. The Allure of Travel

[skip this section if you want to get right to the trip]

If you follow my Twitter account, you’ve seen me posting lots of photos of adorable penguins, humpback and killer whales, icebergs, and majestic polar landscapes. That’s because I was in Antarctica to kick off 2023, going solo (well, along with about 200 other travelers on the ship) on a trip I’ve long wanted to do. When I say, “long wanted to do,” I am going back to childhood, where my passion for travel began in wood-paneled libraries in the homes my mother cleaned, as I sat in a window seat looking through atlases and slowly turning a large globe on an ornate wooden stand, my finger tracing continents and countries whose names I’d never heard. Travel for us, in my working-class family, was an occasional drive back to the hard-scrabble farming village from which we immigrated, usually for a wedding or a funeral or to see relatives. “Vacation” was not a word we used to describe those rare journeys.

It was my early love of reading that transported me to exotic lands and whetted my young appetite to someday see the world. There was also Mr. Bolduc’s ninth-grade geography class at South Junior High (yes, we once taught geography in schools) that built on my early interest, fueled by Mr. Bolduc’s passion for other cultures and places. We didn’t do dry recitations of capital cities and list the principal industries. In language our adolescent brains could process, we learned that values and morals and ways of walking through the world are contextually shaped, that assumptions we make about life might not hold up elsewhere, and that we should approach difference with wonder and curiosity. Still one of the best classes I’ve ever taken.

Later, my high school mentor, Mrs. Collins, would send me postcards and even letters from Africa and Asia and then, when back in boring old Waltham, would sit and show me pictures she had taken, feeding my hunger for travel. I was still in college when Pat and I were dating, and I remember standing on the Mass Avenue Bridge in Boston one warm summer night. We were just beginning to realize we were a “thing” and had started to share our hopes for the future. I remember leaning on the bridge railing and looking up at the sky and saying that I would travel the world someday, hinting that maybe she would want to come along. That was a very aspirational claim in that moment, as I was working construction to pay my tuition, trying to hold together my thirdhand car, and could hardly afford the pitcher of draft beer we had just shared at the old Elliot Lounge.

In college, I found some company selling spring break trips to Daytona, and if I could sell ten of them, I could go for free. Travel, here we come (Daytona for me, back then, would have been akin to Antarctica on the exotic scale)! I sold the ten trips, but when the time came, I needed the money and cashed in my ticket. Travel, you’ll have to wait a bit longer. By the time I graduated, I had saved just enough to do the classic backpacking trip around Europe. And I mean “just enough,” as we camped out almost the entire time, and I paused my trip for two weeks to help build a house in Switzerland in return for food, a warm place to sleep, and laundry. But it was glorious; I was young enough to not even register the hardships, met fun people, and was thoroughly hooked.

When I was in graduate school, I signed on to help a Slavic languages professor chaperone a trip to what was then the Soviet Union at a time when very, very few Americans ventured there. My backpacking trip to Europe wonderfully affirmed what I had so long read and, at some level, knew about Paris and Athens and London. In contrast, the USSR was mind blowing. On that trip, and a successive one two years later, we moved through a largely closed society, always trailed by an Intourist agent, and experienced life in a society fundamentally different from ours in every possible way. We visited the cities that were the settings of the Russian literature I had devoured as an English major, walked the streets at midnight (no place safer than a police state with a dedicated “follower”), took the fabled Trans-Siberian Railroad to Novosibirsk, went south to the Silk Road, and walked through bazaars in Tashkent and Samarkand and felt like we had time travelled back to 1650 (the Kalashnikovs and RPGs for sale in the bazaar notwithstanding).

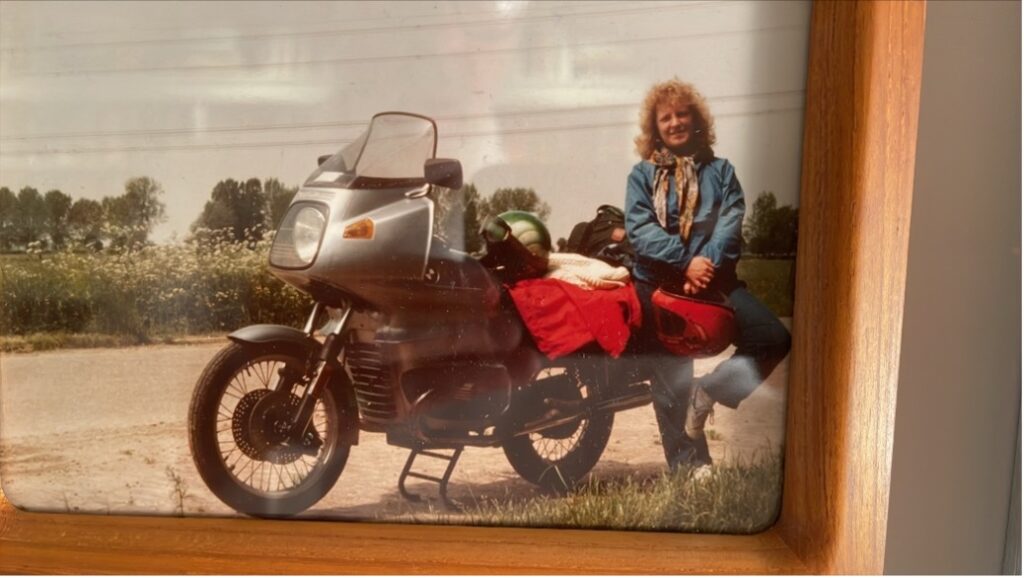

For Pat and me, after food and shelter, we would make trade-offs to travel. A later model car versus a trip to Europe? I can keep that clunker running; give me Hyde Park. Indeed, our first trip together was to London, and by the last day, we had run out of money. I scalped two tickets to Shakespeare’s The Tempest so we could eat that night before our trip home the next day. Another time we borrowed a friend’s motorcycle in Belgium and explored with no plan.

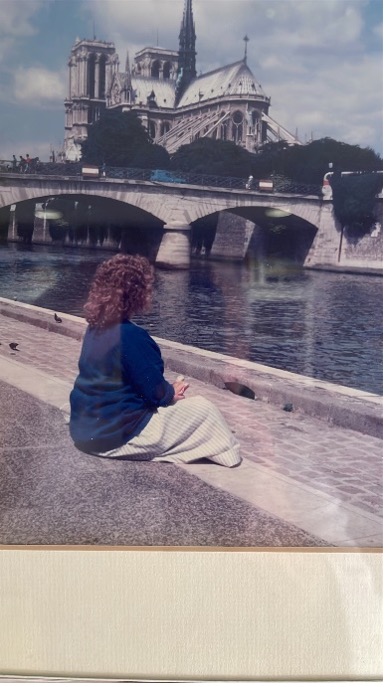

When Pat was pregnant with Emma, our first child, I found a good deal to Paris on Tower Air, a charter airline, and we sat engulfed by the cigarette smoke of French teenagers coming home from a summer in the U.S. I was sure the noxious effect was taking points off our unborn child’s eventual SAT scores. While the next few years consisted of driving trips in a minivan (ugh, I know) with car seats (Hannah had arrived), strollers, a dog, and more, as soon as the girls were old enough, we dragged them to Europe.

Travel was a parenting philosophy for us. We wanted our girls to move through the world with a sense of wonder. We wanted their reflexive reaction to the new and different to be “Let’s see what that’s all about!” and not to be fearful or suspicious. Now in their 30s, they are intrepid and adventurous travelers in their own right, and we have discovered that if we offer to take them on incredibly interesting trips, their very full schedules often and mysteriously open up and they are still willing to accompany us. So I’ve been lucky to realize that dream so long ago offered on the Mass Avenue Bridge with more bravado than budget. Lucky enough to have visited about 60 countries on six continents and to have had wonderful adventures and life-changing encounters.

My remaining continent was Antarctica. The seventh and final box to check. The most inhospitable place on the planet (if you don’t count Philly), the frozen and ferocious landscape explored by legendary, and often ill-fated, explorers of the Heroic Age: Shackleton, Scott, Amundson, and Mawson. Getting there required a long journey to the tip of South America, then two days across the Drake Sea, the worst waters in the world and graveyard of hundreds of ships, and what could be seen and done there would be a day-to-day guess depending on capricious weather conditions, even in the Antarctic summer. Summer apparel would require base layers, a lot of wool, face covering, waterproof pants, a parka, and pockets for Dramamine, sunglasses, and sun block (given the thinner ozone layer). It sounded PERFECT.

With Pat’s blessings, I booked my trip. Not a bit of the adventure appealed to her, and like our girls, she easily gets motion sick. The girls are on academic schedules that ruled them out anyway. This would be a first for me: a solo trip. None of our friends wanted in, balking at either the idea or the cost. And it was expensive. I had sold two motorcycles in 2022 and put the proceeds aside to pay for the trip (remember: given a choice, I’ll always choose travel). After a lot of research, reading reviews and blog posts, and talking to others who have done the trip, I reserved my spot on the Silver Wind, a small ice class cruise ship, with about 220 other travelers and a departure from Puerto Williams, Chile ― at the tip of Tierra del Fuego, a place whose town motto is “The End of the World.” My ship would leave on January 5.

My Antarctica Adventure: Part 2. Who Doesn’t Love a Penguin?

Antarctica in the summer is teeming with life. The confluence of the Atlantic, Pacific, and Southern oceans produces waters so rich in plankton and krill, the base of the food chain, that their green plumes can be seen from space. Marine animals and birds migrate from around the planet, from as far away as the Arctic in the case of the diminutive and champion distance flyer, the Arctic tern, to feed. One of my favorite lines from Annie Hall is something about nature as “one big restaurant.” That’s certainly the case in Antarctica in the summer, with everyone showing up for the buffet. Fish and whales and penguins feeding on krill, seals feeding on fish and penguins, skuas (the jerks of the bird world) feeding on penguin eggs and chicks, and the apex predator that all others fear, orca whales (better known as “killer whales”) helping themselves to pretty much everything that has the misfortune of crossing their watery path (humans aside…at least for now).

Humpback whales, more solo than their killer whale cousins, are everywhere. So much so that if an hour or two went by without seeingone, we thought something must be wrong. There were a large number of scientists and guides on board, happy to talk about their specialization, and there were enrichment lectures each day. Some of us really nerded out on those, though their enthusiasm for things like plankton and rock sediments was such that I sometimes found myself nodding and smiling and backing away slowly. The best was the scientist who enthusiastically shared the details of penguin pooping, including scientific formulas, estimated range (4.5 feet) and velocity (4 mph at the source), and the ways they use this “talent” to enforce social distancing. Thank God the CDC didn’t come up with that one during the pandemic.

Highlights for us included an unusual encounter when killer whales decided to test a humpback. They will occasionally go after a humpback calf, but this was a good size adult. The humpback became agitated and made loud bellowing sounds, and the orcas relented. The scientists had never seen that kind of encounter before. I love the fact that humpbacks really don’t like orcas that much, and there are documented cases of them storming into a hunt to disperse orcas about to kill dolphins and, in one case, lifting a seal out of the water ― and out of the reach of orcas who were closing in the for the kill. Still, for all their viciousness, it’s hard not to love orcas. They are a matriarchal species, guided by the grandmother, are highly intelligent, can adapt their behaviors, communicate as a team, and are just badass. Sort of like the University Provost team these days.

However, the penguins really are the star of the show in Antarctica. Unbelievably cute and comical, with a delightful waddle and form, they have no predators on land, so they care not at all about humans. Often, they would divert from their well-trod “penguin highways” and join us on our prescribed pathways. Because we were instructed to keep 15 feet of distance, we sometimes had to back up; or, when they simply decided to stop on our path and look around, all human traffic had to stop and wait for them to get on their way. We saw more than one stand-off between penguins and skuas, predatory birds that look like brown seagulls on steroids. They patiently wait for a chance to seize a penguin egg or chick. They also harass other birds until they vomit, grabbing that regurgitated food for themselves. Charming animals.

The researchers tried to defend skuas (“Hey, everyone has to eat!”), but we were pretty much having none of it. Gentoo penguins have evolved to lay two eggs, a wonderous example of nature adjusting to circumstances and the impact of the skua on colony health.

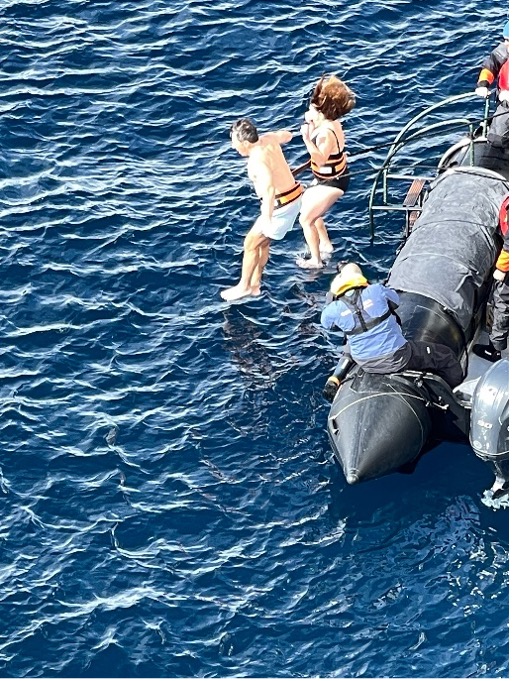

I found myself especially taken with the albatross, an amazing and prodigious flyer, often skimming the wave tops in a perpendicular fashion and riding air currents across vast distances. There were many other bird species, seals of course, one sighting of the elusive minke whale (we think), and lectures on the wonderous and often microscopic creatures that thrive in the coldest waters on earth. Lest anyone doubt the veracity of that last claim, a number of my fellow travelers did the Polar Plunge, with a harness and rope securely attached for when their limbs went into shock and they needed to be pulled out of the water.

I did a polar plunge once through a hole cut into a frozen Vermont pond, part of a fundraiser, and swore then I’d never do it again. So I did not feel compelled this time, and based on the comments of those who did do it, I’m pretty sure that will be their last time too.

I read Ed Jong’s marvelous 2022 book An Immense World on the way down, a delightful look at animal sensory abilities. One has to be struck by how limited we are in or own sensory abilities (okay, we score pretty high for sight acuity), how little we understand and feel the ways other animals experience the world, and how magical is the ability of an Arctic tern to find its ways across thousands of miles, or the ability of humpbacks to use infrasound to communicate across whole oceans (yep, whole oceans!), or the ways deep sea creatures adapt to life in utter blackness. The ways that animals have adapted to Antarctica’s extremes are astonishing. We’d last five minutes. If it was summer.

The animals were pretty great.

My Antarctica Adventure: Part 3. The Ferocious Beauty

I read somewhere that people go to Antarctica for the animals but return for the landscape. For the ice. Generally speaking, I’m more of a city and town guy than a nature guy. I like a majestic mountain, a deserted beach, or a good blizzard as much as the next person, but 9 times out of 10, I’ll take a Paris café over a campfire dinner, an ancient ruin over an ancient desert, and painted ceilings over “painted” canyon walls. Of course, I knew this was going to be a nature trip, and I was eager to see the glaciers, icebergs, and aforementioned creatures. After spending almost more money on cold weather gear than the actual trip, I was hoping for extreme weather, wanting a “real Antarctica experience” like those described by those early explorers ― minus the frostbite, snow blindness, and early death, of course. I had done so much reading I knew this was a place of extremes: the worst seas, the lowest temperatures, the highest wind speeds. As more than one commentator said, it is the closest thing to another planet we can experience on earth. I was ready.

I wasn’t ready.

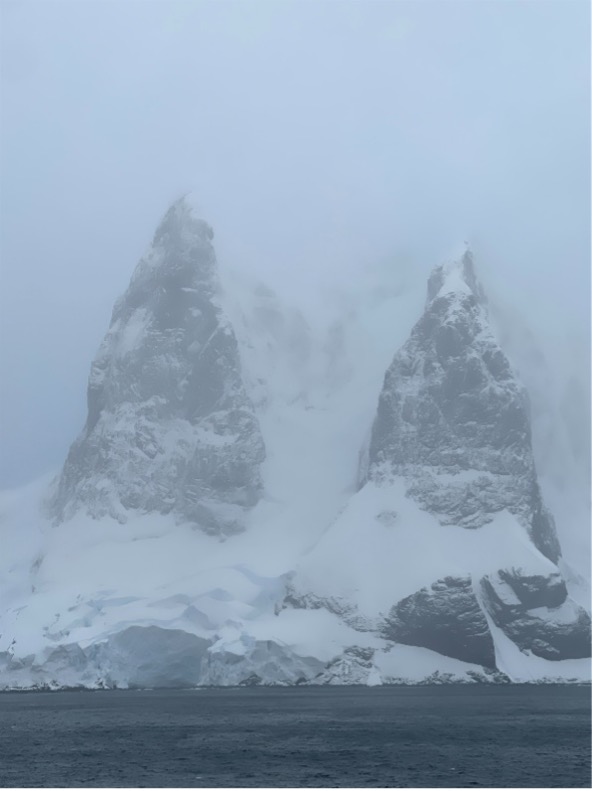

Antarctica overwhelms. First, the scale is astounding and quickly dwarfs anything man-made. Glaciers go on for miles, with rifle shot cracks echoing off nearby mountains as the glacier calves new and immense icebergs. The icebergs themselves are objects of endless fascination. Many are larger than the ship or whole buildings, revealing only a small portion of their actual size. They came drifting out of the fog, they lit up like beacons in the morning sun, they shifted through hues of blue depending on the light, and they revealed different textures depending on if a surface had been sculpted by wind or waves. And then they sometimes flipped, creating massive waves and revealing new shapes.

The mountains, ancient volcanic peaks, often rise sharp and saw-toothed. Over millions of years, glaciers have shaped them with endless variety. At almost every turn, we came upon another unnamed peak that would be the star attraction in any of the 50 states. Like the icebergs, their character changed depending on the light, the fog that often enshrouded them, or the way the wind spiraled snow from their tops.

Then there is the weather. We went from eerie polar fog to bright blue skies to blizzard conditions all in the same day. Hiking on a sunny day, we actually broke a sweat. When glacial winds would kick up, often with no warning (called katabatic winds, they flow down the slope of glaciers, picking up the cold of ice that can be miles deep and move with ferocity), the temperature might plunge 30 degrees and have us scrambling to add layers.

We navigated the Lemaire Channel, sometimes called Kodak Canyon. It was narrow and picturesque, with a howling 50-knot wind and icebergs all around us and the sharp-sided peaks shrouded in fog. We rode zodiacs through newly broken up pack ice, gliding between icebergs at water level. Visiting a penguin colony in a blizzard, my iPhone’s interface so slowed in the icy cold that I held a hand warmer to the back of it. I also put foot and hand warmers in my boots and gloves before leaving the ship. The weather is its own dramatic character in the play that is Antarctica; some would argue the protagonist.

Then there is the sea, the weather’s active coconspirator. The Drake Passage is fabled, the confluence of three oceans with no landmass to slow down the polar winds that circle the continent and act as the engine room for the rest of the world’s climate. Big rolling swells kept our ship moving up and down in ways that sent a lot of people to their cabins and the comfort of seasickness medication. Instead of heading south to Antarctica in a straight line, the captain charted a big sweeping arc of a course to stay east of a massive and menacing low pressure front to our west and had the ship’s stabilizers deployed. I’ve never suffered from seasickness and was lucky to not be laid low, but many others were less fortunate. The passage back was worse, as we fought our way into the wind, with the bow rising and plunging, the latter sending a shudder throughout the ship. Ice formed on rails and windows. I had the front facing library to myself for most of the time.

Anyone walking anywhere had to keep “one hand for the ship,” grabbing railings and furniture to stay upright (it did make it look like a ship of drunks, which I should have captured on video), and barf bags were distributed along all the rails on each deck. Seats at dinner were easy to come by, and plates and glasses would occasionally go sliding off tables with a great crash. Some of the crew who had done multiple crossings said that was one of the worst (a week earlier, a sister ship did the Drake in a massive storm with 100-knot winds and was “hammered,” to use our captain’s technical term). It’s easy to see why the Drake is legendary.

My Antarctica Adventure: Part 4. The Journey Unplanned

Antarctica doesn’t care. Nothing about it works for us. It is not our place, and that can be said for very, very few places on the planet. Its scale, its power, its extremes, its capriciousness, its potential for violence are utterly humbling. As someone who had visited before told me would happen, some passengers quickly retreated to the bar and inordinate socializing. There was refuge to be had in very human comforts, the company of others, and the reassuring confines of the ship. Others, and I include myself here, wanted to stay in that humbling space and more fully feel the place. I did not write even once during the trip, my usual way of making sense of things. I didn’t want the rational sense-making of writing to prematurely close off that increasingly rare way of being in the universe. I was reminded of the many accounts of astronauts who come back from space changed, with a newly discovered reverence for the universe and their place in it. This experience of Antarctica, in its immense scale and ferocious beauty, had some of that feel.

A handful of people said they felt their insignificance, and I shared that sense, though I’d use “humbling” to describe it. It didn’t feel like insignificance per se. Because it also felt connected. Connected without ego ― that was the letting go and not wanting to rationally process the experience. It’s a little of what I imagine religious or mystic experiences to be. It’s what people who take psilocybin often describe, if you read Michael Pollan’s book You Can Change Your Mind. At one point, I found a quiet corner of one of the lounges by myself and watched the fog shrouded mountains slide by and started to feel quite emotional. I mentioned this to a couple of people who reported the same. One woman, an Australian, said she was in a kayak and started to cry and said, “I’m Australian! We don’t cry; and I went from crying to outright sobbing.” Someone else described it as neither sad nor happy, but just feeling deeply moved and overwhelmed beyond words.

I had a hunch ― only a hunch ― that Antarctica might be a spiritual space. While not a religious person, I have long felt the connectedness of things in a way that I associate with spirituality or mysticism. Ironically, even as the world feels more broken than ever, I have felt more conviction around relationship, community, connectedness, and moral complicity. I didn’t go to Antarctica looking for affirmation of that intuition, but I suspected it might be a place to test or explore it.

Also, the world has felt a bit wearying for a while now. My oldest sister passed away in August after a long illness. Professionally, in my role as SNHU’s president, leading during these Covid years has been incredibly gratifying (an honor really), but also exhausting. Humans seem to be regressing rather than progressing (see Ukraine, climate crisis, American politics), and my usually sunny optimism has been sometimes challenged. I had some vague sense that I needed this place to get reconnected, to regain perspective, and put aside my ego and just be.

In Antarctica’s power and majesty, I found what I needed. It wasn’t some grand religious conversion or spiritual awakening, though the comparison of penguins to the nuns of my Catholic upbringing was irresistible. Aside from posting photos on the painfully spotty Wi-Fi connection, I stayed off the grid. Despite predictions from my family and friends, I did not make 200 new friends. I purposefully dined alone, and while friendly with others (we had an assigned zodiac group), I only socialized at the close of the trip once we left the continent and were re-entering the world. I was first intrigued by traveling solo, but by day three was sort of freaked out by it and didn’t like it, and then broke through that slightly panicky feeling and embraced my solitude. I committed to trying daily meditation and stayed with it for a change (my attempts in the past have been comically bad). While I missed people, especially Pat, I relished the solitude.

This was hardly an original experience. A lot of people I know turn to nature when the world is too much with them, to borrow from Wordsworth. We have friends that describe a forest or a deserted beach or a mountaintop as “their church.” That makes sense to me, and I don’t think I’ve been attentive enough to time unplugged, out of civilization, off technology, and simply being in space unspoiled or unshaped by human hands.

If the woods of New Hampshire are like church for friends, Antarctica was like a cathedral for me. Indeed, what started like a grand adventure and trip somewhere along the way came to feel like a pilgrimage, in which progress is marked not only by nautical miles but by the interior distance travelled. One can do Antarctica by skipping the Drake and flying directly to an airfield on the continent, but I came to think of the Drake as the necessary rite of passage in and out, the travail that must attend all good pilgrimages. The Drake was part of the process. After all, you can drive the famous Camino de Santiago across northern Spain, following the medieval pilgrim’s route, but the point is to walk it.

My Antarctica Adventure: Part 5. The uncomfortable questions

The connectedness that was so powerfully part of the Antarctica experience has a dark side. While Antarctica’s scale overwhelms any individual human being, our collective impact as a species poses dire threat to the continent, and the ways we live as a species is very much connected to the ways life is unfolding in Antarctica. We now live in the Anthropocene, the geological epoch that starts with the human species and has accelerated with our presence in almost every part of the planet. We have overrun the place, and the rapid warming of the planet is being felt in Antarctica too. Glaciers are melting too fast, and those amazing icebergs are majestic but also a warning sign. Ice shelves are the glacial end zones that extend out over the ocean, and their presence slows the movement and melt of glaciers. They are now breaking apart in worrying ways, as evidenced by those massive icebergs we saw. Scientists are worried about the Thwaites Ice Shelf, the size of Florida, and signs that it may be destabilized. Should it break off and melt, ocean levels might rise as much as 2 feet, and its destruction would destabilize the rest of the western ice sheet with catastrophic effects globally (https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/antarcticas-collapse-could-begin-even-sooner-than-anticipated/).

People loved the pictures of the penguins I posted on Twitter. They are incredibly charming. They are also in danger. The large gentoo penguin colony we visited is in trouble, as higher temperatures mean more evaporation, which means more snowfall. With more snow on the ground, the penguins struggle to keep eggs dry and thus viable. Chicks that are born are not yet well insulated, and if they get wet in those temperatures they quickly perish. The scientist who led our visit to the colony worries that it is in trouble; we saw no chicks and very few eggs, while the short window for breeding and incubation is quickly closing. Summer in Antarctica is cruelly short.

Disruptions to the environment there are changing the conditions faster than evolution can address, so animals are trying to adapt, and many are now struggling. I think we all came away with a greater sense of urgency around the health of Antarctica and the state of the planet’s climate generally. I read Cal Flyn’s Islands of Abandonment: Nature Rebounding in the Post-Human Landscape while on the trip (when it takes four full days to get to or back from a place, you can squeeze in a fair bit of reading). As she points out, a doubling of the human population has led to a tripling of consumption. We need to arrest the increase in the temperature of our atmosphere before the planet’s feedback loops get locked into irreversible and catastrophic change. Otherwise, the massive flooding we now see in the West, the “once in a hundred years” hurricanes that now wreak havoc across the Southeast every year, and the droughts that are already making vast regions of the U.S., India, Australia, and other countries uninhabitable will feel quaint.

And we had just taken planes and a ship, with a massive carbon price for our enlightening experience. The irony is not lost on me. Each of us on that one week on board the ship exceeded the annual carbon footprint of the average European. That doesn’t count the impact of our multiple flights there and back. About 10,000 people visit Antarctica annually, so the collective impact is that of a European town of 10,000 people for a year. In the end, that will have no real impact on the future of Antarctica, and maybe the collective consciousness raising will even have a much greater positive offsetting impact, but as an individual trying to be conscious of my individual responsibility, it was hard not to feel a bit hypocritical. Buying carbon offsets, as I routinely do now when traveling, helps, but it still didn’t feel quite right, and it is an indirect act, while the black smoke of the ship’s smokestack was an all too immediate reminder that our presence had a cost.

The other slightly White Lotus discomfort of the trip was the stark relief cast on race and privilege. The ship largely reflected the planet’s wealth and racial disparities, with the passengers, scientists, and ship’s officers overwhelmingly White, while the crew, servers, stewards, and cooks were overwhelmingly people of color. Antarctica is an expensive trip ― certainly more than I had ever paid for any trip I’ve taken ― and those who can afford to go more than once displayed their sense of entitlement and superiority. I watched impatient passengers become exasperated because their table was not yet set. A young couple had a meltdown about a missing item, berating a bartender and demanding to see a supervisor, and then after continued escalation, sheepishly finding the item buried deep in a coat pocket. The apology was meager, at best. All the while, those working the ship maintained their composure, grace, and dignity. If I were in their shoes, I might have fed those jerks to the orcas. There were lots of lovely people on board, and I witnessed many pleasant and gracious interactions, but a fair number of my fellow travelers made my decision to maintain my solitude a good bit easier.

It was a reminder to me that my love of travel has consequences and complications.

Finally….

What would I counsel someone who asked if they should go?

I’ve been now, so who am I to suggest others should not? Minimally, I guess I’d say to do so as a conscious traveler, finding ways to offset the impacts of that decision, to be a better human being both for the planet and for those who travel there to feed their families instead of feeding their lust for adventure. And if going, to give oneself fully over to the experience. And then when home, fight for Antarctica, as I will do now.

Would I go again?

It was so powerful an experience, it’s tempting to immediately answer yes. But right now, the answer would be no. It’s not a “been there, done that” response. It’s the opposite. It will take me quite a while to know what that trip really was for me. Antarctica may have done all it could for me or all that I can fairly ask of it. If it’s fair to use my pilgrimage analogy, one doesn’t just do the laundry, pack the knapsack, and set out on another pilgrimage. This has to set for a while.

All I know in this moment is that Antarctica is like no other place on Earth.