Confronting Racism, Past and Present

Posted on February 11, 2019

Our Board of Trustees meets in mid-winter for what we have called a “learning retreat,” going with my leadership team to a place where we can expand our thinking, to learn from some other area of work or industry, and to engage with thinkers and doers in other fields. One year it was Washington, D.C., where we did a deep dive into policy. Another year it was Silicon Valley to engage with new technology. Last year it was LA, where we visited SpaceX, heard from experts in entertainment, and met with Mayor Eric Garcetti. This past week we went to Alabama, to the cradle of the Civil Rights Movement in Montgomery and Birmingham, a fitting place to think hard about diversity, inclusivity, and equity. For most of us, maybe for all of us, it was the single most powerful experience of our time at SNHU.

I’m still processing why it was so. Almost everything we learned we knew at some level, intellectually, but this felt more visceral, often like a punch to the gut and a clasping of the heart. We know that the gun violence of a place like Chicago is out of control and exacting a terrible toll on the children and young people who live in what is effectively a war zone on American soil, but then Arne Duncan joined us with a group of the young men from his Chicago CRED program and we heard the reality of their lives. One had been shot ten times. Billy, the learning coach, had served twenty years for the murder of one of Arne’s best friends and the basketball hope of the neighborhood (a story told in ESPN’s 30-for-30 episode “Benji,” in which Billy appears). The story of the dinner he then had with the victim’s family was a knee buckling story of redemption and forgiveness – not a Hallmark version, but raw and true and ongoing. It’s a story I’ll never forget and one I really can’t recount here – I’m not good enough a writer to do it justice.

Arne shared that in the elementary school classrooms he can ask kids to raise their hands if they know someone who was shot and every hand goes up. He asks them to keep their hands raised if they know five people who were shot — all hands remain up. Ten people? Most hands. Fifteen people? More than half the hands. Twenty people? Half the hands. Think about it – these are little children in an American city. If they were white children, we would have a massive government effort to address the problem. This was a gut punch moment.

We spent time with our colleagues in Birmingham, one of our first urban eco-system learning pilot sites, and had a panel with the amazingly talented team Mayor Woodfin has assembled to address Birmingham’s challenges, including a similar wave of gun violence in the city’s poorest neighborhoods.

Not coincidentally, these are the same neighborhoods that were “redlined,” set aside for Blacks, as official city planning policy.

I had always heard the expression and assumed it was a tacit understanding. It was instead official policy, planned, and its effects are still being felt decades later. Arne’s program in Chicago aims to give young men an alternative to the violence, through work pathways. In Birmingham, we are working to create educational pathways to work through LRNG, our newly acquired community impact group. Billy made a simple and yet deep insight: if you live in a war zone and fear for your life, you carry a gun. If your little sister is going hungry and there is no work, you do whatever it takes to get money to buy food. If you live with incessant fear and hopelessness, you self-medicate through drugs or alcohol. These are rational choices when seen through that lens. Arne and others doing the hardest work imaginable in the hardest places in our country are trying to create hope and a different set of rational choices. I hope that our work with the city of Birmingham will provide a pathway to education, and connect talent with opportunity.

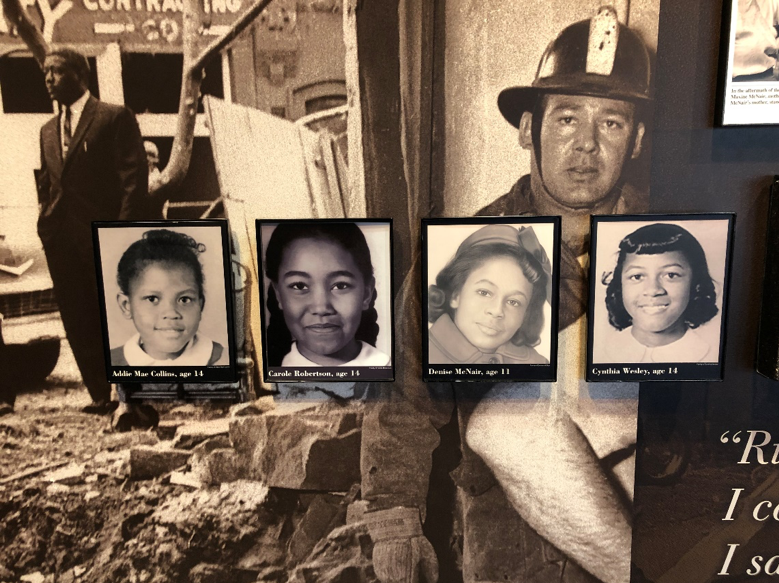

While in Birmingham, we visited the sacred ground that is the 16th Street Baptist Church, where in 1963 white supremacists planted a bomb that killed four little girls.

This storied church is where the heroes of the Civil Rights Movement met, and often preached, including Dr. Martin Luther King, the resolute Fred Shuttlesworth, an amazing man who is not as widely known as he should be, and Ralph David Abernathy, and where the 1963 Children’s Crusade was organized.

We have all read about the heroic struggle for equal rights, but there was something about being in the place that was incredibly powerful. One feels a kind of gravity, the weight of a history that suddenly feels less distant or abstract. It was a feeling I’ve had on the battlefields of the Somme or in the Killing Fields of Cambodia — the presence of those who haunt these places. It was true of Kelly Ingram Park, right across the street from the church and the site of the demonstrations where Theophilus Eugene “Bull” Connor had dogs released and fire hoses used on marchers.

The images from the church bombing and the brutal repression of the marchers made headlines worldwide, sparking outrage across the U.S., and led to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Voter suppression and an ongoing attempt to undercut the act, including demonstrably false charges of widespread voter fraud, are stark reminders that the most basic civil rights remain under threat even after all these years.

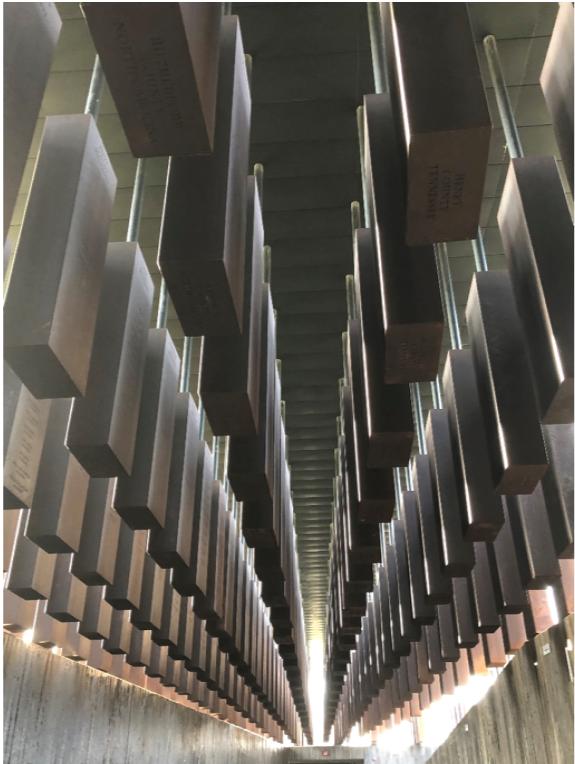

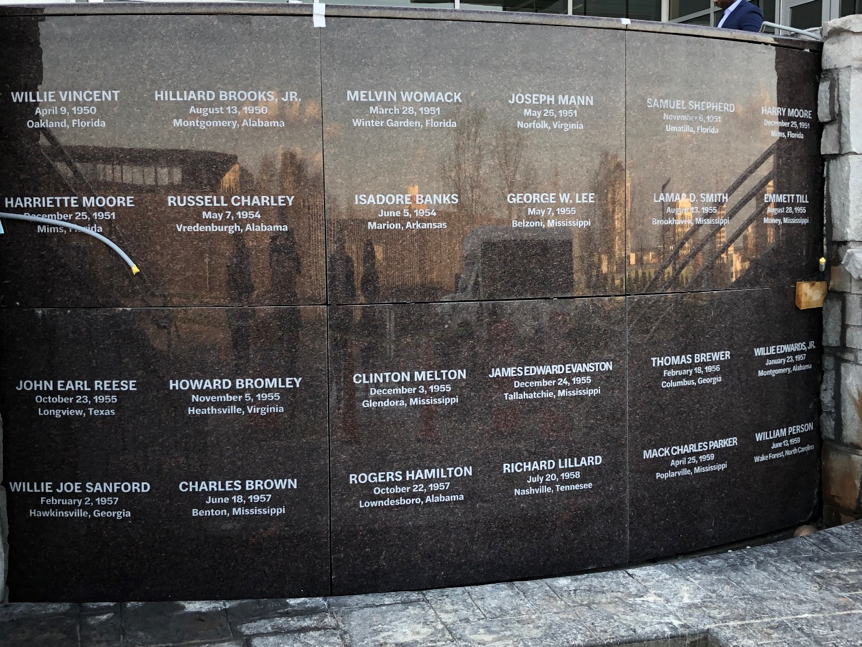

If there was any doubt of that fact, it was shattered by our visit to the newly created National Memorial for Peace and Justice, a stunning memorial to all those killed by racial terror, including thousands of lynchings, in the 19th and 20th centuries. It is the first time I’ve seen in the U.S. a formal coming to grips with the racial hatred of our past in the way one sees in Berlin, which lays bare its guilt around the Holocaust.

Every metal piece, reminiscent of tombstones, represents a county and the names of those murdered there. While they are mostly from the southern states that enslaved people, New York, Oregon, California, and Illinois are among the northern states also represented. Racism knows no boundaries in America then or now.

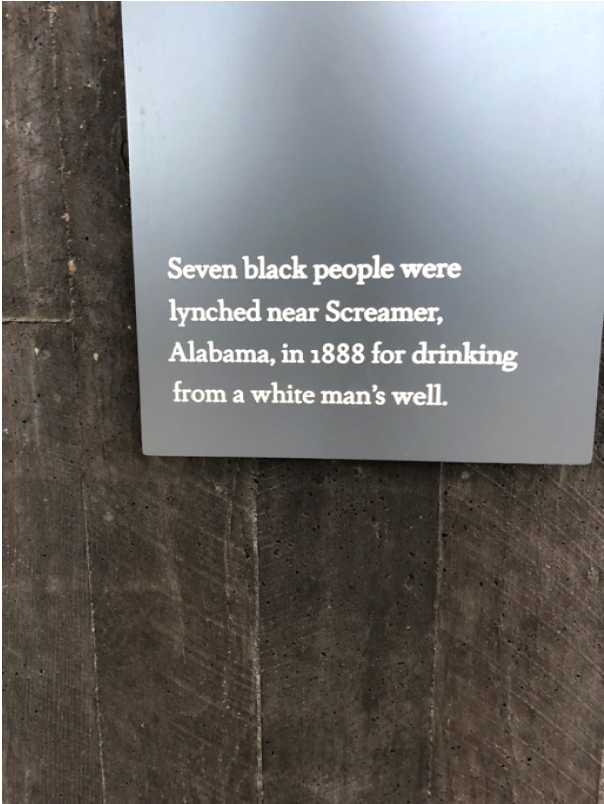

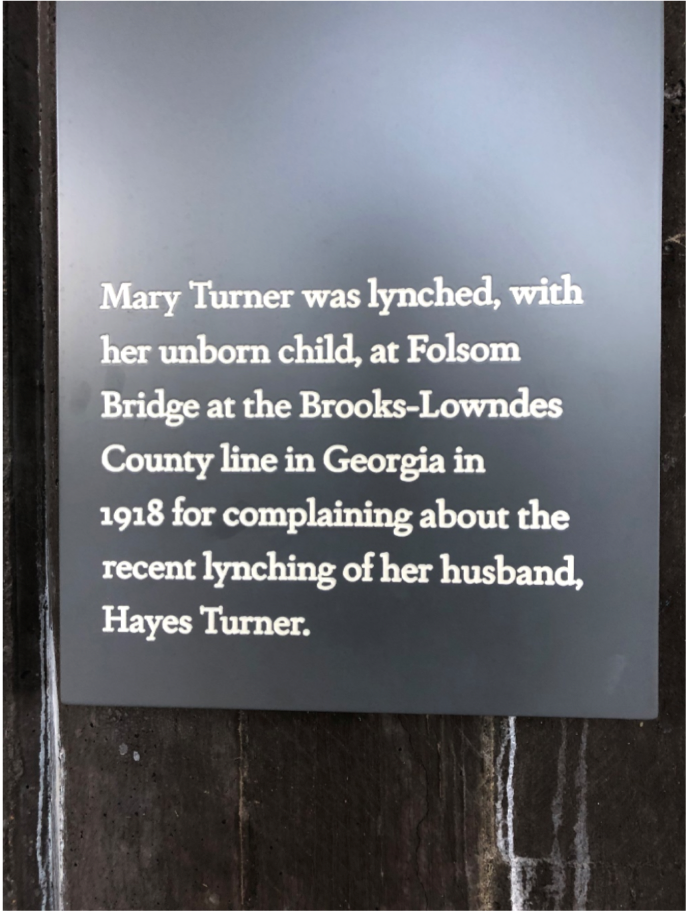

The “crimes” for which people were murdered are shocking.

Lynchings were not rare. The Memorial is stunning in visually and physically capturing the scope of the multi-decade domestic terrorism that created a mass migration north, ethnic cleansing in today’s parlance.

Lest we take some comfort in the notion that these were the acts of some small, psychotic group of terrorists, the nearby Legacy Museum reminds us that thousands of people would turn out to see the violence, bringing children and whole families. Postcards were made and sold. As Bryan Stevenson would remind us, the perpetrators of this systemic terror were not just the uneducated and backward. Complicit were the best educated politicians, business people, clergymen, and yes, academics. And that history is not so distant, extending into my lifetime.

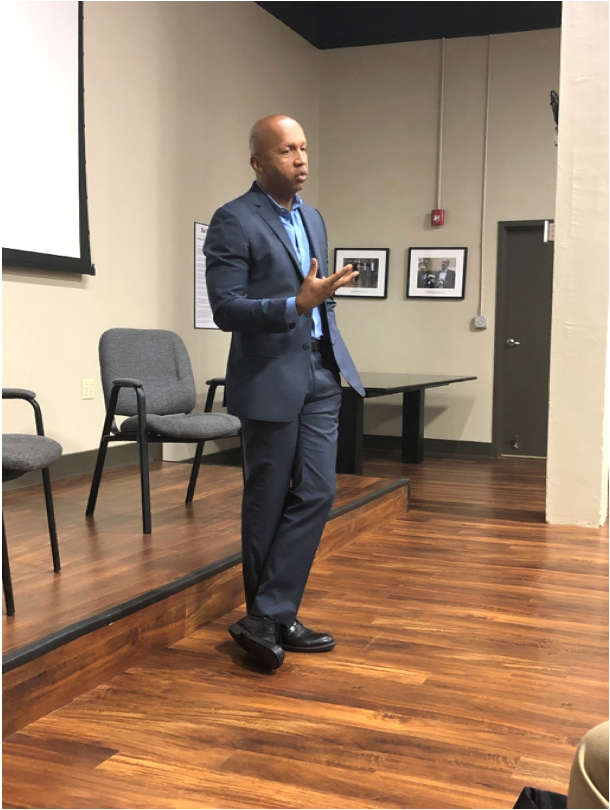

The Memorial and the Legacy Museum were the brainchild of the aforementioned Bryan Stevenson, the crusading lawyer and author of Just Mercy. Founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, Bryan has fought against the death penalty (which overwhelmingly reflects racial bias in its application) and mass incarceration. The Museum draws a clear and unequivocal line from slavery to racial terror to mass incarceration and a deeply racist criminal justice system. Later that evening Alabama put another Black man to death, a jarring and vivid reminder that the injustice remains that close.

Bryan met with us and gave a talk that was at once enraged and inspired. The MacArthur Prize winner was an inspiration, a master storyteller, and reminded us that however hard the challenges are today, they pale in comparison to the fights and the suffering that was endured by those who came before and that it is to them that we have a responsibility to continue the struggle for civil and human rights.

It’s how we honor their sacrifice.

How elevated and inspiring the fight can be was made clear to all of us when we spent over an hour with fabled Judge Myron H. Thompson, the first Black federal judge in Alabama. We sat in his courtroom, the courtroom where Judge Frank Johnson ruled in key civil rights cases, including the Rosa Parks case that struck down segregation in public transportation and the ruling that allowed the march from Selma. Judge Thompson, who has also ruled in famous cases, including Roy Moore’s Ten Commandments case and Planned Parenthood vs. Bentley, reminded us that in this melting pot of a country (some would say “salad”), it is the Law that acts as the pot, that keeps it all together. He reminded us that we were sitting in seats once occupied by Rosa Parks and Dr. King. It was absolutely inspiring and that old beautiful 1930s courtroom, witness to so much history, seemed like church.

As we walked back to our hotel, one member of my team, with tears still in her eyes, said, “I thought I knew. This was like a 2×4 to the side of the head.” At dinner, someone else said, “I’ve never cried so many times in one day, both out of sadness and inspiration.” It was against the background of these remarkable three days that the Board of Trustees unanimously approved our new Strategic Plan for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusivity, which we will release in the coming weeks. They did so because it is a superb plan. They also did it with a deep and abiding resolve that SNHU should play its part in countering this country’s long and ongoing racism and genocidal origins. The Legacy Museum begins with American Indians, the far too often neglected origin story steeped in bloody genocide against a whole people, acknowledging that we have so far to go as an institution and as a country.

On our evening news, the embarrassment that is Virginia politics right now, and in the chants of “Don’t shoot” that ring throughout American cities, we have stark reminders that before we can have reconciliation, we need truth. The truth about America’s ongoing racism is hard to bear, as all who were with us this week would attest, but it did not feel defeating. It felt freeing and empowering and humbling. As it does in so much of its work, SNHU will now put its resources into doing its part. At a time when American higher education is seen as part of the problem, we have to be part of the solution. Access is a starting point and we’ve worked hard on that part of the calculus of hope. With purpose and determination, we will focus on equity, diversity, and inclusivity.

I am proud to be a student at this college of leaders who provide inspiration, guidance, and examples of what our world can accomplish. Your standards inform everyone of possibilities. How a set of principles that does not judge people by the color of their skin, but by their character is an awe-inspiring compass. If we start by changing the historical perception that provides a perspective from all versions (e.g., Spanish and Native American), it can be the change catalyst. Most of our history books taught in elementary only give one version of the past. I find looking through a complete cultural lens aids in determining one’s own understanding that results in obtaining the whole perspective. Thank you for your eloquent words in relaying such a tragic history and the inspiring words of new purpose and passion-driven change.